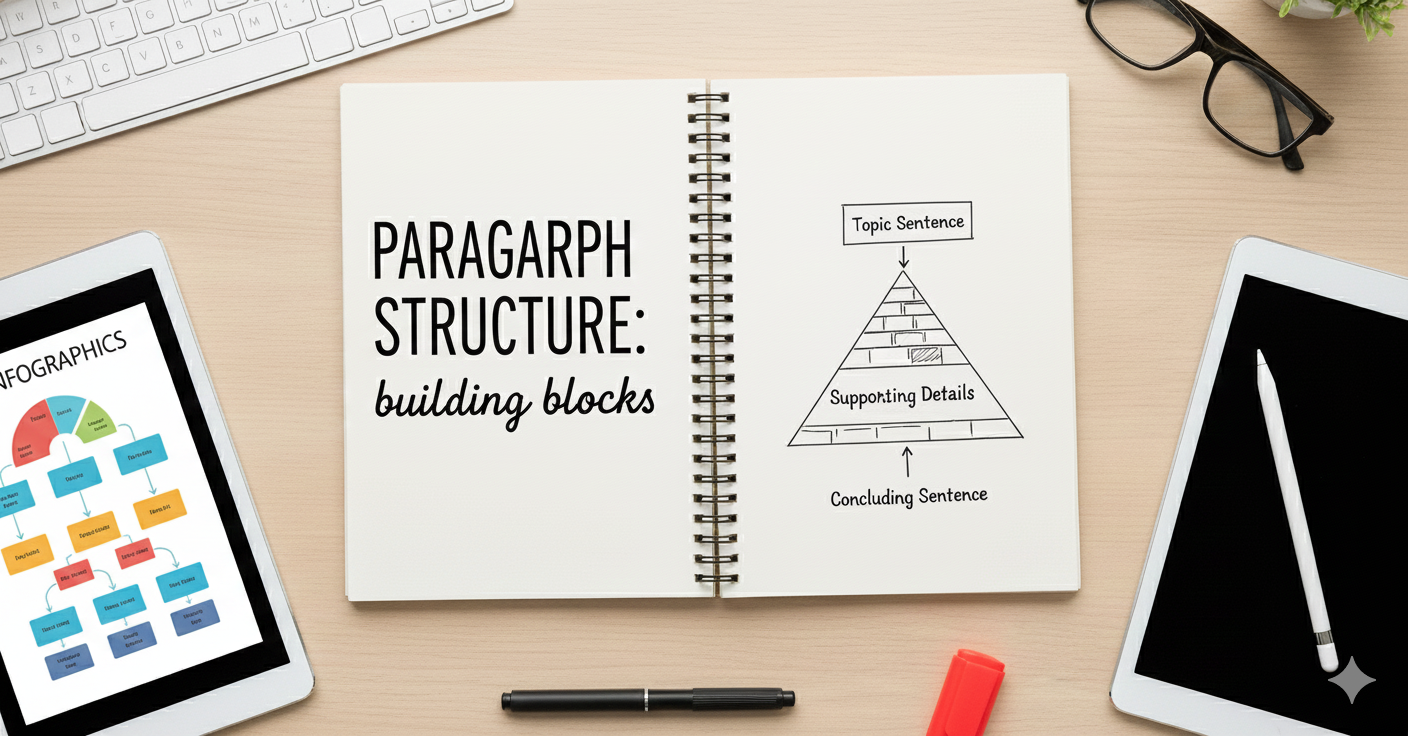

The Art of Paragraph Structure: Building Blocks of Clear Writing

Master paragraph structure to transform your writing. Learn PEEL method, topic sentences, transitions to organize ideas for maximum impact.

Here's an uncomfortable truth: most people don't read—they scan. Studies show that readers typically consume only 20-28% of words on a webpage. In business documents, that number barely improves. Your brilliant ideas? They might never reach your audience if they're buried in walls of text.

The solution isn't writing less. It's structuring better.

Paragraphs are the fundamental units of written thought. Master their structure, and you master the art of guiding readers through complex ideas. Get them wrong, and even simple messages become incomprehensible. Today, we're diving deep into paragraph craft—the overlooked skill that separates amateur writing from professional communication.

The Anatomy of an Effective Paragraph

The Topic Sentence: Your Paragraph's North Star

Every paragraph needs a leader. The topic sentence announces your paragraph's main idea, giving readers a roadmap for what follows. Without it, readers wander lost through your prose.

Weak topic sentence: "There are several things to consider."

Strong topic sentence: "Three factors determine project success: clear goals, adequate resources, and team commitment."

The strong version tells readers exactly what to expect. They know three factors are coming, and they know what those factors address. This mental preparation dramatically improves comprehension.

Supporting Sentences: Building Your Case

After establishing your main idea, supporting sentences provide evidence, examples, and explanation. Each one should directly relate to your topic sentence. If it doesn't, it belongs elsewhere.

Think of supporting sentences as lawyers presenting evidence. Every piece of evidence should support your case (topic sentence). Irrelevant tangents confuse the jury (your readers) and weaken your argument.

The Concluding Sentence: Closing the Loop

Not every paragraph needs a formal conclusion, but longer paragraphs benefit from closure. Your concluding sentence can:

- Summarize the main point

- Link to the next paragraph

- Emphasize significance

- Call for action

The key: don't just repeat your topic sentence. Add value by showing implications or connections.

The PEEL Method: A Proven Framework

The PEEL method provides a reliable structure for crafting coherent paragraphs:

P - Point

Start with your main point—your topic sentence. Make it clear and specific. This isn't the place for mystery or suspense.

E - Evidence

Support your point with concrete evidence: statistics, examples, quotes, or logical reasoning. Evidence transforms opinion into argument.

E - Explanation

Don't assume readers will connect the dots. Explain how your evidence supports your point. This is where you show your thinking.

L - Link

Connect back to your main argument or forward to your next point. Links create flow between paragraphs and maintain coherence throughout your document.

PEEL in Action

Point: Remote work increases employee productivity for knowledge workers.

Evidence: A Stanford study of 16,000 workers found that remote employees were 13% more productive than their office counterparts.

Explanation: The productivity gains stemmed from fewer distractions, eliminated commute time, and the ability to work during personal peak hours.

Link: While productivity increases are significant, they're only one factor in evaluating remote work policies.

Paragraph Length: Finding the Sweet Spot

The Digital Reality

Traditional academic writing favors longer paragraphs—often 100-200 words. But digital reading has changed the game. Online readers need shorter paragraphs for several reasons:

- Screen fatigue makes long blocks of text painful

- Mobile devices display fewer words per line

- Scanning behavior dominates online reading

- Attention spans are shorter in digital environments

Context-Dependent Guidelines

Email and web content: 1-3 sentences per paragraph. White space is your friend.

Business reports: 3-5 sentences. Balance detail with readability.

Academic writing: 5-8 sentences. Develop complex arguments thoroughly.

Technical documentation: 2-4 sentences. Prioritize clarity and quick reference.

The One-Sentence Paragraph

Sometimes, one sentence deserves its own paragraph.

Use single-sentence paragraphs for emphasis, transitions, or dramatic effect. But use them sparingly—too many create a choppy, disjointed feel.

Unity and Coherence: The Twin Pillars

Unity: One Paragraph, One Idea

Every sentence in your paragraph should relate to a single controlling idea. When you find yourself writing "On another note" or "By the way," you're probably violating unity.

Lacks unity:

"Our Q3 sales exceeded projections by 15%. The marketing team launched three successful campaigns that generated 10,000 qualified leads. Susan from accounting is retiring next month after 20 years with the company. We should celebrate these wins while planning for Q4."

Susan's retirement, while noteworthy, doesn't belong in a paragraph about sales performance.

Coherence: Creating Logical Flow

Coherent paragraphs guide readers smoothly from sentence to sentence. Achieve coherence through:

Repetition of key terms: Repeating important words creates conceptual threads.

Pronoun references: Use pronouns to refer back to previously mentioned nouns.

Transitional expressions: Words like "however," "furthermore," and "consequently" show relationships.

Parallel structure: Similar grammatical patterns create rhythm and connection.

Organization Patterns: Choosing Your Structure

Chronological Order

Perfect for processes, histories, or narratives. Start at the beginning, proceed through time.

Example opening: "The project began with market research in January. By March, we had developed prototypes. Testing commenced in May, leading to our August launch."

Spatial Order

Describe physical spaces or objects systematically—left to right, top to bottom, inside to outside.

Example opening: "The new office layout maximizes collaboration. The entrance opens into an welcoming reception area. To the left, glass-walled meeting rooms encourage transparency."

Order of Importance

Lead with your strongest point (most common) or build to it (creates suspense).

Most to least important: Ideal for business writing where readers might not finish.

Least to most important: Effective for persuasive writing that builds to a climax.

Compare and Contrast

Two approaches work well:

Block method: Discuss all aspects of A, then all aspects of B.

Point-by-point: Alternate between A and B for each comparison point.

Cause and Effect

Start with causes and explain effects, or begin with effects and trace back to causes.

Example opening: "Three factors caused the server crash: outdated hardware, insufficient maintenance, and unexpected traffic spikes."

Problem-Solution

Present the problem, then offer solutions. Particularly effective in business writing.

Example opening: "Customer complaints have increased 30% this quarter. Our analysis reveals three addressable issues."

Transitions: The Connective Tissue

Between Sentences

Smooth transitions between sentences maintain flow within paragraphs:

- Addition: moreover, furthermore, additionally, also

- Contrast: however, nevertheless, on the other hand, yet

- Cause/Effect: therefore, consequently, as a result, because

- Example: for instance, specifically, such as, including

- Emphasis: indeed, in fact, certainly, above all

- Sequence: first, next, then, finally

Between Paragraphs

Paragraph transitions require more than single words. Use techniques like:

Echo transitions: Repeat a key word or phrase from the previous paragraph.

Bridge sentences: Create sentences that simultaneously reference the previous idea and introduce the new one.

Question transitions: Pose a question that the next paragraph answers.

Summary transitions: Briefly recap before moving forward.

Common Paragraph Problems and Solutions

The Wandering Paragraph

Problem: The paragraph starts with one idea but drifts to another.

Solution: Identify where the drift begins. Split into two paragraphs or delete irrelevant content.

The Underdeveloped Paragraph

Problem: A topic sentence followed by insufficient support.

Solution: Add evidence, examples, or explanation. If you can't, reconsider whether the point deserves its own paragraph.

The Overstuffed Paragraph

Problem: Too many ideas crammed into one paragraph.

Solution: Identify distinct ideas and give each its own paragraph. Your readers will thank you.

The Disconnected Paragraph

Problem: The paragraph doesn't connect to surrounding content.

Solution: Add transitional elements or relocate the paragraph to a more logical position.

The Repetitive Paragraph

Problem: The same point restated multiple ways without adding value.

Solution: Keep the strongest statement, delete redundancies, add new supporting information.

Special Considerations for Different Formats

Email Paragraphs

- Front-load critical information in the first sentence

- Use bullet points for multiple related items

- Bold key dates, numbers, or action items

- Keep paragraphs to 2-3 lines on mobile screens

Report Paragraphs

- Begin sections with overview paragraphs

- Use subheadings to break up long sections

- Include data paragraphs that interpret figures

- End sections with summary or transition paragraphs

Web Content Paragraphs

- Use the inverted pyramid: most important information first

- Incorporate keywords naturally for SEO

- Break up text with subheadings every 2-3 paragraphs

- Consider pull quotes for emphasis

Presentation Slide Paragraphs

- Limit to one main idea per slide

- Use parallel structure for bullet points

- Keep paragraphs to 3-4 lines maximum

- Support text with visuals

The Revision Process: Perfecting Your Paragraphs

The Paragraph Audit

Review each paragraph asking:

- Can I identify the main idea in one sentence?

- Does every sentence support this main idea?

- Is the paragraph the right length for its purpose?

- Does it connect logically to surrounding paragraphs?

- Would reorganizing sentences improve clarity?

The Reading Test

Read your paragraphs aloud. If you run out of breath, sentences are too long. If you sound choppy, combine some sentences. If you lose track of the main idea, the paragraph lacks focus.

The Scan Test

Read only the first sentence of each paragraph. You should be able to follow your argument's progression. If not, strengthen your topic sentences.

The Reverse Outline

After writing, create an outline from your paragraphs. Each paragraph should represent one clear point in your outline. Paragraphs that don't fit reveal structural problems.

Advanced Techniques for Paragraph Mastery

The Power of the Pivot Paragraph

Use transitional paragraphs to shift between major sections or ideas. These paragraphs acknowledge what came before while preparing readers for what's next.

The Climactic Paragraph

Build tension through a series of increasingly important points, culminating in your strongest argument. Save this technique for persuasive writing.

The Circular Paragraph

End where you began, but with deeper understanding. Reference your opening in your conclusion to create satisfying closure.

The Question-Answer Pair

End one paragraph with a question, begin the next with the answer. This creates engagement and smooth transitions.

Your Paragraph Transformation Toolkit

Great paragraphs don't happen by accident. They result from deliberate choices about structure, organization, and flow. Every paragraph you write is an opportunity to guide readers clearly through your thinking.

Start with these fundamental practices:

- Write clear topic sentences that announce each paragraph's purpose

- Maintain unity by dedicating each paragraph to a single idea

- Vary paragraph length based on your medium and audience

- Use transitions to create smooth connections

- Choose organization patterns that serve your content

Remember: paragraphs are thinking made visible. When you structure them well, you're not just organizing words—you're organizing ideas in ways that make them accessible, memorable, and persuasive.

Master the paragraph, and you master the essential building block of all effective writing.

Ready to transform your AI-generated content into natural, human-like writing? Humantext.pro instantly refines your text, ensuring it reads naturally while bypassing AI detectors. Try our free AI humanizer today →

Related Articles

Your Complete Guide to the Grammarly Plagiarism Checker

Discover how the Grammarly plagiarism checker works to ensure originality. Learn how to use it, interpret reports, and see how it compares to top alternatives.

The 12 Best Free AI Detector Tool Options in 2026

Discover the top 12 free AI detector tool options to verify your content. Our guide compares accuracy, features, and best use cases for writers and students.

Top 12 GPT Zero Alternative Tools for 2026: A Practical Guide

Searching for a GPT Zero alternative? Explore our detailed list of 12 top AI detectors with real-world examples, accuracy insights, and pricing comparisons.